G20 Executive Talk Series

September 2016

The Silk Road

Authored by: Dr Oleg Preksin

The New Dimensions for the Great Silk Road

All of Eurasia should become the territory of accelerated growth and sustainable development could be secured by the rational combination and prudent use of its enormous natural resources, production assets, scientific and technical potential, financial and human capital from East and West, North and South.

The almost two-year-old commitment of global leaders “to lift the G20’s GDP by at least an additional two percent by 2018” (G20 Leaders’ Communique. Brisbane Summit, 15-16 November 2014), even backed by the 2016 Summit priority “to build an innovative, invigorated, interconnected and inclusive global economy and explore new ways to drive development and structural reform” (message from President Xi Jinping on 2016 G20 Summit in China), is becoming difficult to perform. “In an era of peril and many challenges…times of turmoil” (UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s Remarks at the St.Petersburg International Economic Forum, 16 July 2016), divergent economic development and exhaustion of the old sources of growth, ongoing trends towards fragmentation of foreign trade and investment market, geopolitical tensions and uncertainty, the implementation of the above commitment requires a proactive search for new drivers of global growth and integrity. One such driver is the Chinese One Belt –One Road (OBOR) initiative, which has met with great attention and broad support almost everywhere.

The OBOR official concept, released in March 2015 by the China’s top economic planning agency—the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Commerce of the PRC and titled “Vision and Actions of Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”, provides a great deal of creativity and flexibility to all the interested parties. The framework character of this document with minimum details and clear declaration that OBOR is open to all nations and not limited geographically is explored by various stakeholders, promoting their vision of this mega-project.

For example, the Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce (SRCIC), founded in Hong Kong last December “to renaissance the Silk Road and to enable business participation in the investment and trade opportunities it offers”, brought together high level representatives from 39 countries

as founding members and is now creating five organizations to work within the OBOR initiative. These are the eSilkRoad, Silk Road International Development Fund, Silk Road Think Tank Association, Silk Road Commerce and Trade Exposition Park and the International Silver Exchange Center. All five are supposed to form integral parts for the Chinese initiative, providing a brand new platform for interactive connectivity and financial services for ‘Belt and Road’ construction, becoming “the decision-making references for industry development and project cooperation”, an instrument to boost cross-border commerce and improve the real economy.

![]() An extensive network of transport corridors and other logistic facilities on the whole territory of Eurasia should form the basis for TEP project.

An extensive network of transport corridors and other logistic facilities on the whole territory of Eurasia should form the basis for TEP project.![]()

One can also see different OBOR versions like the New Great Tea Road—modern replica of another caravan route from China to Europe in the XVIII-XIX centuries, which passed through the territory now belonging to Mongolia and covering most of Russia. Tea Road was in the same row with jade, salt, cinnamon, tin and wine routes, and was second only to the Great Silk Road in the terms of turnover.

The OBOR concept is actively discussed between China and Russia. The leaders of the two states reached consensus on tapping cooperation potential and advantages, intensifying bilateral ties in energy, high-speed railway and infrastructure, aerospace and aviation, manufacturing and agriculture, investment and finance and other fields. Both sides agreed to reconcile the construction of the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and to coordinate the development with other members of the EAEU and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The recent decision on accession to the latter of India and Pakistan increases the SCO population to almost half of the global. It’s probably needless to enumerate all the resources of SCO and EAEU countries but worth to mention that both organizations are open to new members who share their fundamental principles.

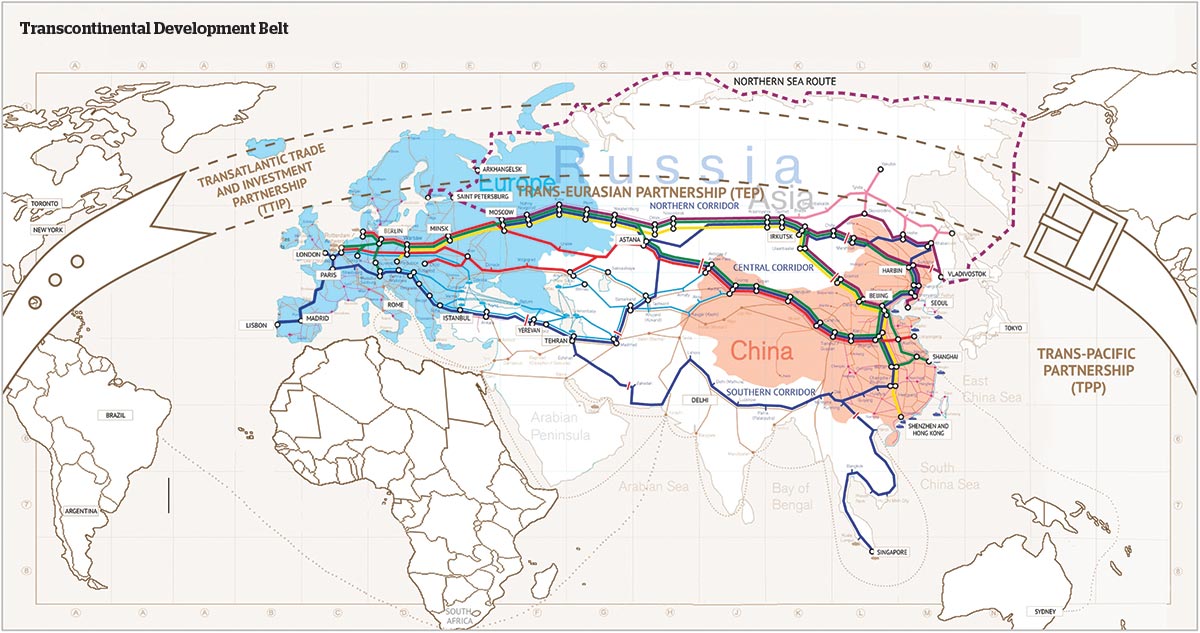

The SCO decision on the accession of India and Pakistan and simultaneous Brexit referendum results indicate the existence of dual trends in Eurasia—for integration and disintegration. This shows the importance of an attractive and reliable platform for the idea of a Single Economic Space from Lisbon to Vladivostok and from Helsinki and Arkhangelsk to Singapore and Mumbai as well. The Trans-Eurasian Partnership could be the proper platform for an idea that covers the OBOR initiative and all its core elements in the upgraded mega-project. Together with the already signed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and still planned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, (TTIP), the Trans-Eurasian Partnership may form some kind of a Transcontinental Development Belt.

The Trans-Eurasian Partnership (TEP), built by the EAEU and SCO existing and new members, by other countries in Asia and Europe, including the EU, as well as the promoted Greater Transcontinental Development Belt (GTDB), linking TEP with TPP and TTIP, is an alternative to the attempts to monopolize the benefits from the technologies of next generation, to create the barriers for the flows of the breakthrough innovation to other territories, with rigid control over the cooperation chains for the maximum extraction of technological rent.

![]() To ensure the proper financial support for the TEP mega-project, not to mention the GTDB, even the resources of the US$40 Billion silk road fund will not be enough.

To ensure the proper financial support for the TEP mega-project, not to mention the GTDB, even the resources of the US$40 Billion silk road fund will not be enough.![]()

An extensive network of transport corridors and other logistic facilities on the whole territory of Eurasia should form the basis for TEP project. The creation of such a network provides not just to upgrade the infrastructure for the ease of communication, but to secure an inclusive and well-balanced development in different areas. And one of the main routes in the new Eurasian transport network will become the high-speed Moscow-Beijing transport corridor with its sequels to Baltic, Atlantic and Mediterranean states in the West and to Pacific, South and South-East Asia countries on the other side. The 770-km Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway segment of this particular route, designed for bullet trains capable of running at up to 400 km per hour – the pilot Russia-China joint construction project, presumably will be followed by other with various participants and different configuration. The land route from Asia to Europe is much shorter than any by sea (and Russia is able to offer the shortest route possible in both cases), but considerably more expensive. And it’s worth to mention, that the existing Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR) utilization ratio reached 100% (that is used to deliver cargoes from Shanghai to Brest and further to the EU). In contrast the utilization ratio of the other main land route going to Europe through Kazakhstan, Central and European part of Russia the experts estimate to be less then 25%. (Eurasian Development Bank Working Paper).

Full use of the central line of Trans-Eurasian transport and logistics corridor does not preclude the construction of its northern and southern branches that may be also commercially valuable. One of such branches—China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor—involves the implementation of about 30 projects agreed by all three parties on the sidelines of the SCO June summit in Tashkent.

It is valid to ask: how can such projects and programs be funded? Who is able to support financially TEP and GTDB mega-initiatives? The answer lies in the field of public-private partnership (PPP), in its development in all forms and at any level: national, regional or global. First of all, it’s worth to apply to conventional long-development banks and similar institutions, as well as to the new ones, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) or the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB). Each of these two has the authorized capital of US$100 billion. The AIIB, where China, India and Russia are the main shareholders, is going to expand its membership from 57 to nearly 100 countries and regions by the end of this year. With co-financing from the World Bank (WB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the AIIB approved this June the first loans for about US$500 in total. NDB is also working on its first block of projects, although the development of project finance in the PPP format, that is inevitable with growing budget constraints, is yet to come for both banks.

To ensure an adequate financing for the project of TEP and GTDB magnitude, it’s worth to replenish conventional fund rising with some special purpose vehicle (SPV). And the construction and exploration in the late XIX—early XX century of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), also known as the Chinese Far East Railway and Manchurian Railway, might provide some useful experience, given the today’s realities.

In the harsh conditions with participation of foreign capital, mainly French and German, CER JSC implemented unprecedented for its time multimodal infrastructure project, which eventually became profitable. The line provided a shortcut from the world longest TSR near the Siberian city of Chita via Harbin (CER built capital) to the Russian port of Vladivostok with outputs to Beijing, Seoul and other major cities. In addition to the large areas received used under long-term concession and known as the CER Zone and the rolling stock, CER also had built its own fleet and conducted regular maritime shipments to Japan, Korea and Chinese costal cities. To finance its development CER has arranged about 20 bond issues that were acquired by the government, but also placed on the markets outside Russia.

To ensure the proper financial support for TEP mega-project, not to mention the GTDB, even the resources of US$40 billion Silk Road Fund will not be enough. Loans and investments from the existing development banks are also of a limited application. So it’s worth to consider the possibility of establishing as SPV specialized mega-fund, that may issue international bonds with partial state guarantees, and to register a major management company, inviting world known financiers and entrepreneurs with an impeccable reputation to its Board. The fund with the management company could be domiciled in one of the leading international financial centers, for example in Hong Kong or Singapore. And the SPV issued bonds may be convertible into the shares of financially supported projects.

The leading partners for TEP are expected to be not only the EAEC, SCO and BRICS states and their business circles, but also the investors from Japan, South Korea and South East Asia, from Western Europe (Germany, France, Italy, for example) and probably from North America – all who cares of Eurasia. Speaking in June at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF), the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon stressed “the critical importance of further economic integration and cooperation in this region.

At the moment, however, we see countries breaking ties and building new barriers. History tells us that this is not the right direction for Europe. We need to strengthen ties and build bridges, instead of building walls”.

All of Eurasia should become the territory of accelerated growth and the sustainable development could be secured by the rational combination and prudent use of its enormous natural resources, production assets, scientific and technical potential, financial and human capital from East and West, North and South. This is the very sense and the main point in TEP and GTDB mega-projects, which should remain open for accession by all the interested parties. “Let’s work together to make this world better” (Ban Ki-moon’s Remarks at the SPIEF, 16 July 2016).

Dr. Oleg Preksin B20 Sherpa for Russia in 2012-2015 is now a member of the B20 Financing Growth and Trade & Investment Taskforces. Vice President of the Association of Russian Banks (ARB) with an extensive banking experience in Russia and abroad. The first Russian director in the EBRD Board, also representing Belarus and Tajikistan. The founding member of the SPIEF Organizing Committee, a member of the Coordinating Committee of the Financial & Banking Association for Euro-Asian Cooperation and of the Eurasian Economic Commission Working Group for the EAEU Integration Mainstream.